What is Pulmonary Fibrosis?

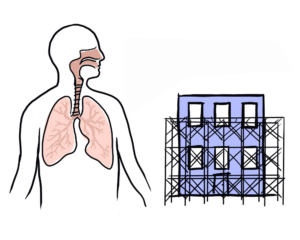

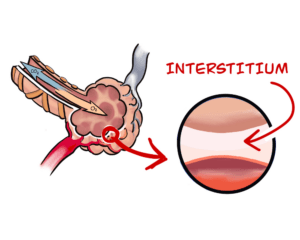

Pulmonary fibrosis (PF) is a family of more than 200 interstitial lung disease (ILDs) that cause inflammation and/or scarring of the lungs.

About 30,000 Canadians live with PF. Approximately half of this group of people have Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF), meaning the cause is uncertain or unknown.

What causes pulmonary fibrosis?

Pinpointing the cause an individual case of PF can be challenging. Known causes include: occupational exposures to asbestos and inorganic dusts, organic compounds (mold, bacteria…) some medications, autoimmune diseases such as scleroderma or rheumatoid arthritis, chemo or radiation therapy. Smoking is not a cause, but it is a known risk factor. Often, there is no identifiable cause.

What are the symptoms of PF?

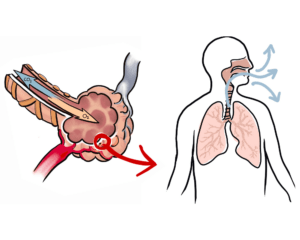

Generally, a feeling of shortness of breath or breathlessness upon exertion is an early sign of pulmonary fibrosis, sometimes accompanied by a persistent cough. Because symptoms can develop very gradually, it can take years before other common respiratory problems can be ruled out.

What to expect as PF progresses

Pulmonary fibrosis is a chronic disease. It behaves differently for each individual. However, one can typically expect that once the fibrosis scars the lung, that piece of the lung is permanently damaged. Ultimately many people with the disease become candidates for a lung transplant. Medication, good nutrition and exercise and emotional support can go a long way towards improving the quality of life of people living with the disease.

More on What is Pulmonary Fibrosis

CPFF Documentary – Breathless for Change

This documentary explores the courage and resilience of people living with PF and uncovers the barriers to accessing equitable healthcare for treatment and disease management.

Understanding ILD in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Scleroderma and Other Connective Tissue Diseases – Dr. Janet Pope

Dr. Janet Pope shares what you need to know about interstitial lung disease (ILD) in connective tissue diseases (such as lupus, scleroderma, myositis) and rheumatoid arthritis.

Living with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis – Meet Zelick

After complaining of a persistent cough during a regular check-up, 66-year old Zelick was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Watch his story.

So you have been diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis…what’s next?

If you or someone you care about is living with pulmonary fibrosis this is a must-watch explainer video that describes what PF is, what you can expect and how to manage your disease.

Read Next…

UHN Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Handout

This handout for people living with IPF and their families provides information on what idiopathic…

Burden of IPF Report

This report reveals major gaps and disparities in care for Canadians living with idiopathic pulmonary…

Pulmonary Fibrosis Patient Guide

Pulmonary Fibrosis Patient Guide (English) Guide du patient sur la fibrose pulmonaire (Français) The CPFF…

Frequently Asked Questions

“That’s an excellent question!” – You will hear this a lot. Do not get frustrated, it’s not your doctor’s fault if he or she does not have the answers. Through fundraising and support, advances in research will help answer those questions.

What causes Pulmonary Fibrosis?

Some of the known causes include occupational exposures such as asbestos and inorganic dusts, organic compounds such as mold and bacteria, and certain medications. Smoking, although not a cause, is a known risk factor for the development of PF. For many patients there is no identifiable cause, and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis falls into this category.

What are the symptoms of PF?

Chronic breathlessness is the most common and recognizable symptom. A dry, hacking cough may also develop. Over time, you may experience fatigue, a loss of appetite and weight-loss.

What are key indicators for concern?

“That’s an excellent question!” Research has not yet identified all key indicators, however if you have severe shortness of breath and trouble breathing and cannot recover within 10 minutes, present yourself to your local hospital in emergency or dial 911.

What is the prognosis?

Prognosis is highly variable, and is dependent on the underlying cause. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in particular has an unpredictable path, with a life expectancy (without a lung transplant) averaging 2-5 years from the date of diagnosis.

Should I maintain an active lifestyle?

Absolutely. It is essential to remain physically active to the best of your abilities, but you should consult with your doctor to ensure this is done safely. Having a good exercise capacity is especially important if lung transplant is being considered.

Can I travel?

Yes, however be cautious of high altitudes (i.e. airplane travel) as this may result in low oxygen levels and medical oxygen is not available everywhere – check with your physician before you travel. If you are placed on the lung transplant list, you will need to remain in close proximity to the transplant centre at all times.

What about alternative medicines?

This is a personal choice and you should always discuss with your doctor before starting any prescription or non-prescription medications.

What can I do to help myself?

Listen to your doctor. Avoid risk of infection. Make sure your vaccinations against influenza and pneumonia are up to date. Stay positive!

Build and maintain a close circle of family and friends. If you are placed on the transplant list their support will be especially important.

How can I help someone who is suffering from PF?

Just provide the support and help they need, please do not consider it an imposition because they really do need you.

What can I do to protect myself from the smoke and haze of wildfires?

We’d just like to take this time to remind everyone, especially those with compromised lungs that with summer comes the risk of wildfires across Canada. The smoke and haze caused by these wildfires can contain very small particulate matter that can be harmful to Pulmonary Fibrosis patients. These PMs are so small that they can bypass the respiratory protection measures and infiltrate the alveoli causing further lung damage and possibly resulting in further scarring.

*There is very limited evidence on the use of respirators as an individual-level mitigation approach during wildfire smoke events. The evidence found is equivocal. The effectiveness of respirators as a public health intervention has not been fully evaluated.

The BC Centre for Disease Control has issued a paper on protection from the effects of wildfires which can be accessed through the following link: http://bit.ly/1Zc2J65

This paper has a number of cautions and lots of information and I recommend that all PF patients read it for their own protection. Here two important pieces of information from that paper:

*To provide individual-level respiratory protection during a smoke event, the personal protective equipment must be able to filter very small particles and it must fit, providing a firm seal around the wearer’s face to minimize hazardous agents from entering the respiratory system around the edges of the respirator. Personal protective equipment that provides respiratory protection includes respirators that either filter air or supply fresh, clean air.

* Respirators with HEPA (P100) filters offer the highest protection, but may be less comfortable as they provide more resistance to breathing. P100 respirators may be slightly more expensive than the N95 respirators, for which retail price is between $13 and $25/box of 20 units3

Surgical masks do not provide any protection from these PM and thus should not be used for long periods of exposure to smoke and haze.

Essentially it is recommended that PF patients stay indoors as much as possible and if they must go out a facemask with HEPA (P100) Filters or N95 Filters should be used as protection. PF patients should not spend much time outdoors during periods of haze and smoke from wildfires. Remember that such haze can extend over 500 km from the wildfire source.

* Source BC Centre for Disease Control paper

#PFQA – Pulmonary Fibrosis Online Question & Answer with a Panel of Experts

Questions and Answers from an online panel of experts hosted by CPFF and Ward Health.

Panel of Expert Respondents

Dr. Martin Kolb: Dr. Kolb, Associate Professor of Pathology and Molecular Medicine at McMaster University, and Director of The Firestone Institute for Respiratory Health at St. Joseph’s Healthcare in Hamilton Canada.

Professor David G Taylor: David Taylor is Professor Emeritus of Global Health and Pharmaceutical Policy at UCL London, UK. Read Professor Taylor’s article “Pulmonary Fibrosis – Care for Patients, Benefit all.”

Robert Davidson: Robert Davidson is President and Founder of the Canadian Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation, a registered charity dedicated to providing education and support for people affected by pulmonary fibrosis.

How can someone with PF exercise when it is difficult to breathe?

Answered by Robert Davidson – Even a little exercise will help. Try walking a little, even just a few houses down the street will help and you will soon be able to do more. The Canadian Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation has a video that can help you exercise. It was produced with the help of respirologists (pulmonologists) and physiotherapists who are experts in the treatment of PF and is available free of charge on our website at www.cpff.ca

Because autopsies find 97% of patients with Simion HPV, should IPF patients not be on anti-virals?

Answered by Dr. Martin Kolb — It is correct that some studies report presence of Herpes virus (HPV and others) in autopsy tissue. However, these findings are difficult to validate and even normal lung tissue is often positive for viral particles. It requires special molecular techniques (called PCR or hybridization) to look for minimal amounts of particles in the samples. The scientific and clinical value of these reports is not yet strong enough to warrant anti-viral therapies. Of course, special situations may cause the treating physician to consider anti-virals.

I do a tremendous amount of coughing, from the time I get up until I go to bed. Is this common? My mother and my sister had this and they did not cough like I do.

Answered by Dr. Martin Kolb – Cough is one of the typical and sometimes first signs of IPF. However, not all patients get cough. It often starts as dry cough and, with more advanced disease, can also be productive of some phlegm. The treatment of cough can be quite challenging and different medications may be needed. Initially, over-the-counter cough medication should be tried.

Is the risk of developing IPF increasing?

Answered by Professor David Taylor — There is some evidence that the incidence of the condition is increasing in countries like the US and the UK, even allowing for factors like population aging. One reason could be better diagnosis. Another might be increased survival with other serious lung disorders. Pulmonary Fibrosis is classified as a rare disease in that the annual rate of new cases is in the order of 1 per 10,000 population. But with an average life expectancy from diagnosis of around four years this means that at any one time there are 100-150 thousand people living with pulmonary fibrosis in North America, and about 200 thousand in the European Union. In total there could be as many as two million with PF across the world, albeit that on average populations are younger in regions like Asia and South America.

Does pulmonary fibrosis only affect people when they get older?

Answered by Professor David Taylor — Most people diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis are aged 50 or above. But its origins can be linked to their earlier lives, and the consequences of PF can impose serious distress on family members of all ages.

Answered by Robert Davidson – – While most patients are between the ages of 50 to 70 at diagnosis there a number of younger patients although theirs tends to be as a result of other factors such as scleraderma.

I have been offered an opportunity to enter a clinical trial. Are there risks? What happens if my symptoms get worse?

Answered by Dr. Martin Kolb — Being enrolled in a clinical trial always offers benefits for patients with IPF. It is well know that even patients who are on placebo in the setting of a trial do much better than patients who are not in a trial. One of the reasons is the close follow-up and attachment to an expert center that is provided by the clinical trial unit. Obviously, drugs at the earlier stage of development may have unexpected side effects. One of the goals of a clinical trial is to learn more about new drugs, both about their good and also bad effects. If you are enrolled in a clinical trial, the study center will closely monitor your health and blood tests and you will have access to the center 24/7.

Can societies across the world afford better therapies for disorders like pulmonary fibrosis?

Answered by Professor David Taylor- There is no doubt in my mind that the answer is yes, especially if their prices differentially reflect each community’s ability to pay. Seen rationally, what we cannot afford to do is to stop innovating. There will of course always be arguments about whether or not particular companies are making too much or too little profit, or whether or not University and hospital based researchers are giving good value for the public and private money they receive. But if we in the long term want humanity to survive, and in the shorter term to relieve the suffering caused to individuals by disorders like Pulmonary Fibrosis and all the many other currently untreatable diseases, we need continuing bio-scientific progress.

All the medicines ever discovered currently cost the world between 1 and 2 per cent of our gross annual income. This proportion has been roughly stable for decades, in large part because once new medicines become established products they can be made and distributed as low cost generics. Human labour, by contrast, is always relatively expensive. Few people say they want unchecked competition to drive down the wages of doctors, nurses and other health and social care workers to poverty levels. At the same time it is in patient and wider public interest terms right to try to ensure that enough is paid for new medicines like better treatments for IPF to encourage continuing high risk investment in ongoing innovation.

Crackles or velcro sounds, are these unique to IPF or even to PF? Are they suggestive of other conditions? If not a sound associated with COPD, then this should be further information for the doctor that the patient doesn’t have COPD?

Answered by Robert Davidson — While crackles and velcro sounds are not entirely unique to PF they would indicate that there is probably a 90% to 95% chance that PF is present and an urgent referral to a respirologist is called for. They do not appear in COPD or other lung diseases.

I have been told that I should be referred to an ILD (Interstitial Lung Disease) unit to confirm the diagnosis and find out what treatments and trials might be available. Is this necessary?

Answered by Dr. Martin Kolb — Any well trained respirologist will be aware and can make a diagnosis of IPF. Of course, ILD clinics usually have a broader expertise in this field and have more experts who have seen many of the more than 100 different disorders that are listed under the term “ILD”. These special clinics are particularly helpful for patients who don’t have a typical presentation, for example who have a non-typical CT image or who are younger than we expect for IPF (anyone younger than 55-60). Many respirologists would seek a second opinion from an ILD center to advise them in the diagnosis and management of IPF.

How does NSIP differ from IPF? Any studies going on for NSIP? Do I need biopsy for definite diagnosis? What is prognosis?

Answered by Dr. Martin Kolb — NSIP (Non-specific interstitial pneumonia) describes a pattern of scar distribution on a CT scan or a pattern of microscopic changes on a lung biopsy. It can occur without any detectable cause and then is caused idiopathic NSIP. It can also occur secondary to causative agents (e.g. drugs etc) or connective tissue diseases (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis or scleroderma). Idiopathic NSIP is typically less progressive than IPF, but it can sometimes also behave in a similar way. Regular follow-up visits and breathing tests will help to monitor the disease and adjust the management plan. Tissue biopsy is not necessary, but can be helpful to distinguish from IPF. To date, there are no trials done at a larger scale for NSIP.

Can new treatments cure pulmonary fibrosis?

Answered by Professor David Taylor — No. Their full potential is not yet known in either the early or later stage disease contexts, alone or in combinations with other agents. The best that can be presently expected is that they will slow the development of Pulmonary Fibrosis, and perhaps that of other fibrotic diseases. They are not without unwanted side effects, and should not be thought of as ‘magic bullets’. But is good news that advances are being made. If we continue to invest in treating rare disorders like PF progressively more effective curative and/or preventive interventions will become available. As we ‘unpack’ both the genetics of given illnesses and the biology of normal immune, inflammatory and other fundamental biological processes we will be increasingly able to treat distressing disorders of all types, rare and common alike.

What treatment options are currently available, or in development, for PF?

Answered by Professor David Taylor — Different types of Pulmonary Fibrosis may respond to different types of treatment. Some patients – resources permitting – might be suitable for lung transplantation and some respond to anti-inflammatory and immuno-suppressant therapies. But in general the options for people with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis have been disappointingly limited. That is why it is exciting that in the past year two new medicines have become available. Pirfenidone acts on fibroblasts, the cells that make connective collagen. Nintedanib also acts as an antifibrotic, via different inhibitory mechanisms. Other innovative therapeutic approaches are either in trial or in earlier stages of development.

Answered by Robert Davidson — There are treatments that can help with some of the symptoms of the disease. These would include exercise, prednisone and perhaps NAC. There are also two treatments approved in many countries that slow down the progression of the disease. One is esbriet (pirfenidone) manufactured and distributed by Hoffman La Roche and Ofev (nintedanib) manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim. Both these drugs are prescribed to patients with mild to moderate forms of IPF. Ofev is not yet approved by Health Canada but that is expected this year.

My GP believes I have IPF and is referring me to a respirologist. What is involved in the full diagnosis? I have heard that a lung biopsy may be done. Is that dangerous as it may cause more scarring?

Answered by Dr. Martin Kolb — Lung biopsies are nowadays only done if there are doubts about the correct diagnosis. No medical procedure is without risk, and the potential risk has to be less than the expected benefit of getting a tissue diagnosis. This is particularly important when other forms of lung fibrosis that could improve with steroids are considered. In general, the risk of a complication after biopsy increases with more advanced disease. The most dangerous complication is a flaring of fibrosis, which would require hospital admission.

Why is there so little known about PF?

Answered by Dr. Martin Kolb — IPF is a relatively rare disease compared to other lung diseases (such as asthma, OPD or cancer) and awareness of IPF has therefore been low. Organizations like the CPFF together with expert physicians are working hard to change this and always need the help of affected patients and their families. With more awareness comes more research funding, which is instrumental in learning more about the complex biological process underlying IPF. Knowing the biology is key to developing new drugs that hopefully will stop the progression of IPF once and forever.

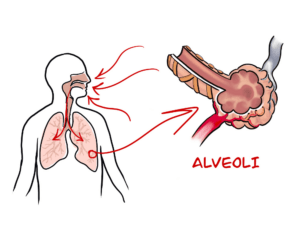

What is Pulmonary Fibrosis and what causes it?

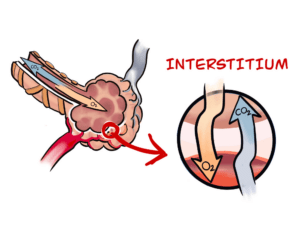

Answered by Professor David Taylor — The processes that cause fibrotic diseases are related to the scarring that occurs when a wound heals. Such disorders involve the excessive and damaging build-up of connective tissue in organs like, for example, the heart and the liver. In the case of Pulmonary Fibrosis (literally, lung scarring) the disease starts in the walls of the alveoli, the tiny air sacs deep in the lung, which thicken and stiffen. It causes symptoms like chronic coughing and problems with breathing.

People with diagnosed Pulmonary Fibrosis have relatively short life expectancies. Some forms of the condition are associated with other lung disorders such as COPD (chronic bronchitis) and appear to be triggered by smoking or breathing in other known lung irritants. But the most common type, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis IPF), is of unknown cause, albeit biomedical advances are now throwing light on the fundamental mechanisms underlying its occurrence.

Answered by Robert Davidson – PF is a disease characterized by progressive and irreversible scarring of the lungs. As the lungs become more scarred it becomes more difficult for patients to properly exchange gases (Oxygen/CO and CO2) and the patient suffers from shortage of breath and the oxygen saturation declines affecting other organs.